Lesson 113

No Stop Diving

By the end of this section, I should be able to answer these questions:

1. What is no stop (no decompression) diving?

2. What is a no stop (no decompression) limit?

3. What do I have to do if I exceed a no stop limit?

4. What is the relationship between depth and my no stop limits?

5. What happens to my no stop limits as I ascend to a shallower depth during a dive?

6. Why is my ascent rate an important part of a no stop dive?

7. What is the difference between a decompression stop and a safety

No Stop Diving

As a recreational diver, you plan your dive so that you can, if necessary, swim directly to the surface without unacceptable risk of decompression sickness. This is called no stop diving. (You sometimes hear it called “no decompression diving,” but “no stop diving” is more technically accurate.)

No Stop Limits

You plan your dives so they are always well within the no stop limits. (You sometimes hear no stop limits called no decompression limits – NDLs). A no stop limit is the maximum time you can spend at a given depth and still ascend directly to the surface. If you exceed a no stop limit, to keep DCS risk within accepted limits, you must make one or more emergency decompression stops. These are stops at specific depths for prescribed times to allow your body to release dissolved nitrogen before you ascend further. In recreational diving, decompression stops are emergency procedures only (you’ll learn more about these in Section Five).

Depth and No Stop Limits

As you’ve learned, the deeper you dive, the greater the pressure on your body. The greater the pressure, the faster nitrogen dissolves into your body tissues. This means the deeper you dive, the shorter your no stop limits.

You can see the no stop limits for each depth in your dive computer’s Dive Plan Mode (your computer may use a different name for this; see the manufacturer literature, or ask your instructor to help you).

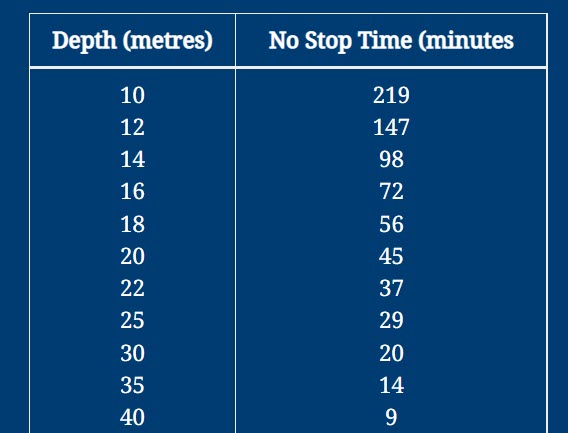

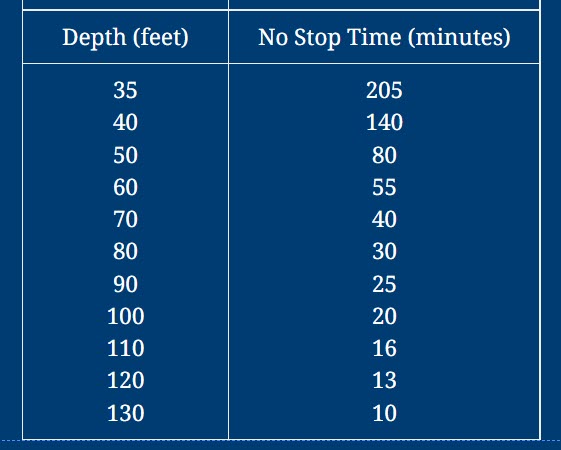

With most computers, you scroll depths in 3 metre/10 foot increments, displaying the maximum time allowed at each depth. You use this information to help plan your dive. Dive computers may have different decompression models. As a result, the no stop times for two different model computers may differ somewhat. You can also find no stop times on the RDP Table and eRDPML.

You can see the relationship between depth and no stop time by comparing them. The times/depths shown are from the RDP Table, and are similar to many dive computers. Your computer may scroll in different depth steps, but the relationship is similar.

Note that your no stop time gets shorter significantly faster as your depth increases. Recall that you also use your air faster as go deeper. Therefore, the deeper you dive, the more frequently you should check your remaining air supply and your remaining no stop time (more about this shortly).

Here’s an example: Suppose you and your buddy descend to 10 metres/30 feet, pause for a moment and then continue to 18 metres/60 feet. At 10 metres/30 feet, your computer would show you have more than three hours no stop time. When you arrive at 18 metres/60 feet, your computer now reads less than one hour no stop time remaining.

During the dive, your computer constantly updates your remaining no stop time based on your dive profile – your actual depths, and your times at each depth – and the limits set by the decompression model.

The no stop time you see when you scroll your computer during dive planning is the time you would have if you stayed at the depth the entire dive. Very commonly, however, you don’t stay at the deepest depth the entire dive. You descend to a deepest point and then slowly ascend as you explore and tour along a sloping reef or bottom.

During the dive, your computer shows the no stop time you have remaining at your present depth. As you ascend, nitrogen absorption slows, so the remaining no stop time will increase. The remaining no stop time will, however, be less than you saw for that same depth during the predive scroll, because you have absorbed some nitrogen.

One of the advantages of dive computers is their ability to calculate more no stop dive time as you ascend. This is called multilevel diving. With dive tables, you must treat the dive as if you spend the entire dive at your deepest depth. This means you’re limited to the no stop time of your deepest depth, even if you actually spend most of the dive shallower. (An exception is the eRDPML.

Although not as versatile as a dive computer, the eRDPML allows you to plan multilevel dives that increase your no stop time as you ascend.)

Here’s an example of the changing no stop times you might see on a typical dive: You and your buddy plan to descend to a reef to 18 metres/60 feet, explore a bit, then slowly ascend following the reef upward to shallower depths. You plan to keep the dive well within no stop times, and plan your air use so you will surface with 50 bar/500 psi.

For planning purposes, you scroll your computers and find that at 18 metres/60 feet, the no stop time is 55 minutes. You and your buddy agree to start up after 30 minutes if you have not already turned due to air use. You notice that the no stop time for 12 metres/40 feet is 140 minutes. The dive goes as planned. After exploring the reef for 30 minutes at 18 metres/60 feet, you and your buddy follow the reef upward. Just before you start up, your computer shows your remaining no stop time is 25 minutes.

As you ascend, the remaining no stop time increases. At 12 metres/40 feet, you see it showing a remaining no stop time of 83 minutes. This is much more time than you had remaining at 18 metres/60 feet, but less than the no stop time you noted predive. This reflects the nitrogen absorbed during your 30 minutes at 18 metres/60 feet. At this point, you have more no stop time available than the length of time your air supply will last. The dive will then need to end based on your air supply. At the appropriate point, you and your buddy ascend, make a safety stop and surface with 50 bar/500 psi in your cylinders based on your air supply, as you had planned.

Ascent Rates and Safety Stops

Most computers and dive tables have a required ascent rate. The no stop time assumes that you ascend at that rate. If you go faster than that rate, you may increase your risk of DCS. Ascending no faster than 18 metres/60 feet per minute, or the ascent rate of your computer (whichever is slower), also helps reduce the chance of lung overexpansion injury. Most computers have audible and/or visual warnings if you ascend too fast.

You’ve already learned that as you ascend from a dive, it is a good habit to make a safety stop for three minutes at 5 metres/15 feet before finishing the ascent and surfacing.

A safety stop is not required to be within the limits of most dive computers’ or tables’ decompression models. You make the stop as a prudent, conservative diver to remain well within your dive computer or table limits. A few computers and tables have a “required” safety stop. With these, because you are nearing the limits, they call it “required” to put more importance on being conservative.

Recall that some problems, such as an out-of-air situation, may call for omitting the stop to reach the surface quickly. In such instances, it is more important to reach the surface safely than to make the safety stop.

As mentioned before, a decompression stop is a stop in your ascent that is required because you exceeded the no stop limits. If you surface without making a decompression stop you would be outside model limits and theoretically have more nitrogen in your body tissues than acceptable. This creates a high risk of decompression sickness. In recreational diving, making a dive with required decompression stops is an emergency procedure only.

knowledge review and quiz

Comments

I'll take you diving!

Copyright © Larry Wedgewood Scuba Instruction All Rights Reserved